Behold—Your Weekend Diversions!

Graydon Carter, Philly Crime Stories, Uzo Aduba, Charley Crockett, and More...

Dear Wags,

The fascinating people in American life are not pedigreed aristocrats but strivers from the sticks who hit town determined to reinvent themselves. This was true long before F. Scott Fitzgerald came around, and the legend endures. Who is Donald J. Trump, of Queens, if not a concocted persona, some douche’s idea of a tycoon? Say whatever you like about him, but do keep talking about him. You can’t say he isn’t committed to the role.

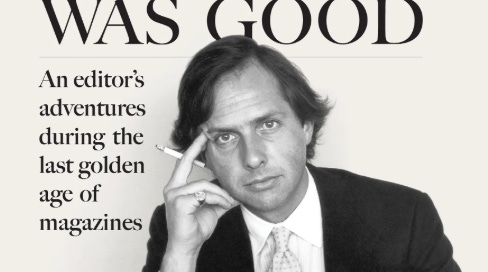

But let’s talk about another turn-of-the-millennium sensation with extraordinary hair: Graydon Carter, an editorial titan from when magazines were Magazines. You may have heard he has a book out. It is a delightful, if melancholy, exercise for the dwindling number of us who came of age when Carter’s influence was at its smoky, martini-soaked, expense-account-covered peak. Because it’s all over, obviously—vanished with fleets of black town cars and the possibility of S.I. Newhouse Jr. covering your mortgage. You might as well be reading about ancient Sumeria.

I never toiled under Graydon, but let’s call him Graydon because low-paid magazine underlings used to do that, with an eye roll and a sigh of exasperation, as if they all knew and put up with him.

Graydon! Anna! Tina! Adam! Jann! Kurt!

We were on a first-name basis with them all, while they were off somewhere, having a marvelous time and winding up in the columns the next day. We traded stories about their imperious demands and idiosyncrasies. We slaved for them, hated them, loved them, and wanted to be them.

They were Editors—to be indulged and suffered under, to emulate and rebel against. You sure as hell ran downstairs for coffee, dumped out the ashtray, and dropped their brat’s forgotten homework off at Collegiate. Your reward was the anecdotes, which you banked for the novel every peon wrote in their head.

“I’m only here for you!” I once told a legendary editor while angling for a raise.

“Now that’s a good one,” he said. Then he laughed me out of his office. “You’re here for me. You’re all just here for me!”

At their best, glossy magazines were aspirational fantasies—a projection of the world as the Editor willed it to be: sophisticated, snarky, wicked, flawless. They were never created by the genuine elite, which makes and hoards the real money, but by those with their noses pressed up against the glass. In the heyday, a lowly writer could delude himself into thinking that all the objects shilled in them—bespoke suits, classic six apartments, second homes, the fancy schools—were not just reserved for the rich and dull, but available to the enterprising and witty. This was the intoxicating fable Graydon sold to the rest of us.

To me, profoundly. The unhappy child from California longs to be interesting. He finds a portal in magazines. They sell an idea of The City—not the grimy, tense, dangerous hole it is in that era, but a gilded place filled with like-minded souls who dressed well and talked like characters in screwball comedies. In this Imaginarium, smarties skewer gauche plutocrats, parvenus, and social X-rays—Leona Helmsley, Roy Cohn, Henry Kissinger, Liz Smith, Gayfryd Steinberg, Anthony Haden-Guest, Donald Trump—and win.

Would it be too much to say that Graydon revived New York? It was hardly a solo project, but he was instrumental in projecting a dazzling image of the place to a new generation of seekers back to the urban hub and transforming it in the 1990s into a brighter, shinier place. In the process, we may have smothered its louche, anarchic qualities, murdering bohemianism with suburban comforts. But as the book says, the going was good.

This is hardly a unique origin story, but I became a magazine person because of Spy, the magazine Graydon created with Kurt Andersen. I remember like it was yesterday, reading a cover story titled “Ivanarama,” which itemized the bad behavior of the first Mrs. Trump. Among her crimes was designing a maternity uniform for female employees at the Plaza Hotel that bore an unmistakable resemblance to a Bozo the Clown costume. I laughed until I wept.

Oh, what words can do—bring you to delirium, bring the bully down a peg, invite you to a party, build a universe. But words, it turns out, aren’t enough. Spy had Donald J. Trump pegged in paragraph one—short-fingered vulgarian, highly leveraged vice king, scalp-tightened self-promoter, debtor-adulterer, floundering casino operator, a fool and a liar and a deadbeat, flyaway-haired mogul and author, creative, hands-on, person-to-person superguy, nobleman lounge singer, a man of obviously limited abilities… and, definitively, a cheeseball. The magazine is now an answer to a trivia question, and Trump is the most powerful man in the world.

Spy knew how to needle its thin-skinned target—“the very symbol of greed, vulgarity and bluster”—but that only fueled his unholy drive. Trump was never slinking back to Queens. Surely Edward Graydon Carter of Toronto—gravedigger for a day, failed railway lineman, aspiring Wodehouse character—understands that better than most people.

To be young in New York is to peer up at the lit brownstone window and feel a keening I want, I want. By the time my generation of magazine makers arrived in the city, the gilded age of New York media was over; we just didn’t know it yet. Rich people like to make money, not indulge journalists. Graydon’s storied tenure at Vanity Fair reflected both the evolution of media, its inevitable decline, and, as one colleague puts it, “one peculiar man’s Catholic tastes”—Anglophilia, liberal politics, snobbery, media gossip, luxury goods, high finance, Hollywood, and what used to be called café society.

Graydon did not invent the high-low bouillabaisse, but he distilled and exalted it, so much so that it now largely defines the sensibilities of the coastal elite. Its obvious foil is the blunt instrument of Trumpian populism. Presently, one side seems to have thrashed the other. Today’s world—coarse, stupid, and not at all amusing—is not the one our editor heroes dreamed up.

That’s hardly their fault. The internet not only crushed magazines, but it also gave vulgarians, short-fingered and otherwise, the definitive upper hand. Remnant mainstream media is cowardly and devoid of humor. Irreverence may be everywhere among its successors, but real wit is in short supply, and they have little impact on a fragmented audience. When it comes to confronting the powerful, it turns out that being a smartass is no weapon at all.

What vulgarians understand about journalists is their yearning to be included. In the glory days of New York media, sarcasm masked all kinds of desire—for money, for a great apartment, for the novel to be published, for that book to be optioned, for an award-winning screenplay, for a producing credit, for glory beside the people you envy and ridicule. To be—at last!—famous, too. I want. I want. I want.

How hilarious and miserable so many of us were, chasing the mirage of Graydon Carter’s New York. You could wear a chalk-stripe suit and affect an accent. You stretch to have your shirts and shoes custom-made and spend your nights drinking whiskey in clubby bars. “Dressing like a major literary figure doesn’t actually make you a major literary figure,” quipped a lock-jawed Vanity Fair lackey I once knew.

How right he was, about almost everybody who made it for the last chapter. There were eccentrics, poseurs, and comedians among us. We weathered volatility and meanness and grueling hours. Too often, we were clever when we should have been kind. Some of us had lucky breaks and snatches of notoriety, but nothing to equal those of the lions we worked for. They stayed at the main table until it was closing time.

Graydon joined the newsletter revolution, but even great newsletters only hint at the glamour that preceded them, a symphony of words, pictures, and heavy paper stock. The Good Magazine was an artistic subversion of commerce, led by a singular, erratic individual of some brilliance and considerable taste. It ended ages ago, but who can begrudge the man of that faded hour anything? It was his party, after all.

Yours Ever,

Peter Fallow

Streets of Philadelphia

Dope Thief (Apple+) and Long Bright River (Peacock). Behold the spawn of Mare of Easttown—two crime thrillers set in the least appreciated corner of Megalopolis. Philly may have won the Super Bowl, but it still has an accent that defeats most actors. Points to Peter Craig’s adaptation of Dennis Tafoya’s 2009 novel for setting the action in the city among people who drink wodder. Two no-account buddies (Brian Tyree Henry and Wagner Moura) pose as DEA agents to rip off drug dealers. Ridley Scott drives the tense, propulsive action from there, with Dame Kate Mulgrew along to steal scenes.

Elsewhere in the Cradle of Liberty, Liz Moore teams up with Nikki Toscano to bring her gripping Long Bright River to Peacock. Amanda Seyfried plays a Philadelphia cop searching for her missing, drug-addicted sister (Ashleigh Cummings) while a serial killer stalks women working the streets. The series was largely shot in New York, which explains why the cheesesteaks look hinky. An appealing star anchors a mystery that stretches longer than the Schuylkill.—Merritt Chase

The Secretary of State, in the Treaty Room, with a Candlestick…

The Residence (Netflix). In some more placid universe, a whodunit about terrible crimes in the White House would demand a suspension of disbelief. On our timeline, this amiable Shondaland product fits right in. Uzo Aduba is Cordelia Cupp—a name that all but winks at you—a quirky sleuth investigating a murder at a state dinner for the Australian prime minister, which explains Kylie Minogue’s presence.

To get to the bottom of it, she teams up with an FBI agent (Randall Park) and navigates a starry lineup of retainers and officials played by Giancarlo Esposito, Susan Kelechi Watson, Ken Marino, and others. Think Knives Out in the Oval Office—at least this time, the cleaving isn’t being done by DOGE.—Janine Skorsky

Boy Trouble

Adolescence (Netflix) and Happy Face (Paramount+). The best Netflix limited series in ages comes from Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham, who deliver a wrenching crime drama set in an unnamed English town. Graham—never better—plays a father whose baby-faced 13-year-old son (Owen Cooper) becomes the prime suspect in a murder investigation. From there, things only get bleaker, as the boy’s thwarted life and growing fascination with the manosphere come to light. Directed by Philip Barantini, the cast includes Ashley Walters, Erin Doherty, Faye Marsay, and Christine Tremarco.

From the other side of the Atlantic, Happy Face takes a milder true-crime approach to the twisted male psyche. Annaleigh Ashford is solid as a woman reckoning with the fact that her jailed serial-killer father is, well, Dennis Quaid—who seems to be hitting his stride playing really bad guys.—Frank Sobotka

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to CultureWag to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.