BookWag Architecture Bonus: Meet the Blob!

The L.A. Desk Surveys the New LACMA. Plus: Great Reads from Gary Shteyngart, Charlie English, Ruben Reyes Jr., E. Jean Carroll, and More...

Letter from the Miracle Mile

Dear Wags,

There are few things we’re more allergic to than the peculiar language of curators. Artspeak is an argot of obfuscation. With its prattle about hierarchies, binaries, volumes, teleologies, hegemonies, and ‘spaces,’ it tries to slap adverbial lipstick on a pig. Occasionally, a thing can simply be a thing—requiring no strenuous academic rationalization. And that thing is not a transgressive subversion of the dominant paradigm or a chromatic revolt against a patriarchal visual lexicon—it’s just ugly.

So a Philistine’s bullshit detector pings when a museum director responds to criticism of his expensive new building by saying the architecture is “not linear.” What does he mean by this? How can a $715 million concrete ectoplasm, cantilevered across Wilshire Boulevard—a scout saucer from an invading alien armada, the Caltrans overpass to San-Nowhere-in-Particular—not, fundamentally, be linear?

Ah, we smell what LACMA director Michael Govan is cooking in response to architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne—who, in an essay for his Punch List newsletter, wrote that the museum’s brand-new David Geffen Galleries, while “thrilling” at some remove, revealed blemishes upon nitpicky closer inspection.

“I noticed uneven execution in every direction,” Hawthorne wrote. “The floor is veined with spidery cracks. The walls are discolored by huge water stains and other flaws.”

Hawthorne was measured in his assessment and praised the ethereal vision of its legendary Swiss architect, Peter Zumthor. It was the clunkiness of the tangible, human-built product he quibbled with:

“Zumthor’s design promised on a level of precision and rigor that the finished product fails, in any number of ways, to reach.”

Govan’s It’s not linear translates to You don’t get it. It’s a curatorial dodge—trotted out for everything from bodily fluid on a canvas to chaotic gallery layouts to leaky pipes. A way of reframing concrete questions as narrative ones: Where you see a grim hardscape or a stairway to nowhere, I diagnose a symbolic intervention. Where you see unwholesome condensation, I spy a meditation on material vulnerability.

Of course, we know what Govan means. Not linear is shorthand for a conceptual reordering—an attempt to liberate museums from nasty imperial hierarchies. But civilians take their museums literally. They walk through them. They climb stairs. They look for the Impressionists. They wonder where the Grecian urns have been moved. A narrative may be non-linear, but the body tends to move from A to B. In architecture, philosophy only goes so far before your feet revolt.

Sophisticated justifications have riddled the labored construction of the Geffen—Govan’s great white whale—like so much black mold.

Upon the museum’s soft opening, these justifications aren’t especially necessary. The new Geffen wing is not ugly. It’s a provocative, often pleasing attempt to reconcile the idea of Los Angeles with mere architecture. Still, it cannot levitate above mundane criticism—as it does above Wilshire Boulevard—on the hot air of artspeak.

Govan’s deployment of linear is confounding. He’s used it to explain both the blobby architecture of the Geffen wing and a similarly blobby reframing of its vast collection, which must now be non-hierarchical. Everything, for instance, must be displayed on one level, because upstairs vs. downstairs implies a value judgment. This is pitched as yet another “reinvention of the museum”—a soft revolution in how mortals enjoy eternal art.

But such trendy deflections are now under fire in Trump’s America. Critics of Govan’s LACMA suspect effete gloopiness in both form and function, undermining one of the country’s great museums. It might be easier to say he approved the Zumthor design because it looked cool.

The most eloquent of the Geffen wing’s detractors is Christopher Knight of the LA Times, who famously dubbed LACMA The Incredible Shrinking Museum. For all the billions it cost to erect, the Geffen wing reduced gallery space—from the 120,000 square feet available in the uninspiring William Pereira complex it replaced to just 110,000. There’s no room inside the mod pancake for curators’ offices. Storage and other essential, if less photogenic, functions have been banished off-site.

Govan has vigorously pushed back. Before the Geffen rose, the museum added the Resnick Exhibition Pavilion and the Broad Contemporary Art Museum—BCAM, not to be confused with its rival Broad Museum downtown. Whatever you make of the result, Govan succeeded where many would have stalled: he drove a megaproject through a bureaucratic thicket and brushed off critics along the way. He’s also floated the idea of dispersing parts of LACMA’s collection to satellite galleries across the megalopolis—an act of democratization, or a subversion of the museum as sacred entrepôt, depending on your spin.

Govan must be feeling vindicated now. Visitors who previewed the new building in late June didn’t bring tape measures; they were mostly exhilarated by the airy, twisting space. (The real test will come when art is hung on its concrete walls.) The Geffen is a big, confident statement in a battered community starved for them. Knight’s review called the new LACMA “sleek, splotchy, jarring, powerful, monotonous, appealing, and absurd.” That sounds like an apt description of its city.

The quaint Victorian dream behind LACMA—and all encyclopedic museums—was to bring together divergent threads of human culture and house them under one roof. Pereira once described his LACMA as “an acropolis of art,” just as Lincoln Center or the Los Angeles Music Center were conceived as acropolises of culture. But in the last half-century, there’s been an academic revolt against that conceit.

A public collection of art implies that some art is particularly worth collecting—and some is not. The hierarchy within a museum, and the way it treats the products of other cultures, is obviously shaped by perspective and bias. Govan and his curators have a point. So did a student activist in my sophomore year of college, who had the maddening habit of repeating Classic to whom?—over and over.

Starchitecture transforms structure into spectacle—the foundational work of art.

Yet it’s a valid question—one modern museums wrestle with, often strenuously. Notions of what’s worthy shift depending on who’s doing the curating. LACMA is trying to address this sticky wicket with architecture and exhibition philosophy, which can be noble. But the general public just wants the Greatest Hits, gathered together in one place. In a seminar, the Big City Museum is a polemic. To the hoi polloi, it needs to be a delightful place to visit.

LACMA is already bowling over the lookie-loos. Starchitecture transforms structure into spectacle—the foundational work of art. The hazard, abundantly pointed out, is that a good building must do this without eclipsing the art. Los Angeles is filled with flashy Statement Buildings. The best of them—like Richard Meier’s Getty Center in Brentwood, a literal acropolis—manage to showcase both the art and Southern California’s natural environment.

The Geffen is LACMA’s long-anticipated clapback to the Getty, and it has certain advantages. It’s a more expansive museum. And it sits closer to what passes for the city’s heart, convenient to public transportation and a host of other major destinations. And so we return to Govan’s old foe: linearity. Los Angeles is often called the Linear City. From above, his museum resembles an inkblot—or a golf course sand trap—plopped onto the vast urban grid.

The Zumthorian vision for LACMA (in early models, it was black—like the neighboring La Brea Tar Pits) is, in fact, an homage to that development pattern. Los Angeles is synonymous with sprawl, but it’s more built-up and orderly than many younger American cities. Its lines and nodes are a legacy of the old streetcar network, not the later freeway system. Its boulevards—long and wide, if not exactly grand—stretch across the megalopolitan basin.

Zumthor’s building, like Los Angeles, is flat and wide. It leaps across Wilshire—the queen of the city’s boulevards—like a freeway. (A few miles west, the 405 does the same thing.) Urbanists will blanch: overpasses tend to create forbidding spaces beneath them—unsavory parking lots for drifters’ tents and stolen shopping carts. But if you squint just right, you can almost reimagine these bridges as triumphal gateways.

LACMA’s imposition on Wilshire—the way it sinuously floats across the boulevard, exposing visitors to dazzling views of the city in all directions—was the most controversial element of its design. It’s also its most crowd-pleasing. If L.A.’s streets are vehicular conduits and fearsome barriers, the museum’s bridging of Wilshire is a triumph for pedestrians. They will stand above the city’s greatest boulevard as conquerors. The space beneath the building, if properly maintained, will offer Angelenos a rare and inviting public amenity: shade.

Hawthorne is correct about clumsiness in some elements, even if most of LACMA’s visitors won’t notice it. The Geffen wing is an unwieldy public works project, whittled away in all sorts of ways by bureaucratic torments. Zumthor, now 82, had never worked in the United States before. He says this—his largest commission—will also be his last American adventure. When Hawthorne interviewed him in 2023, Zumthor said that after so many compromises, “there are no Zumthor details anymore.” Govan was quick to dispute this, but the remark speaks to the difficulty of pulling off a grand projet in California—and fuels the arguments of abundance liberals who call for cutting red tape.

Cruising the boulevards with the top down, soaking in the Hollywood sign and Googie architecture, is now a sentimental luxury.

The exorbitant cost of public works is the bane of every American city—and an acute challenge for Los Angeles, the urban amoeba smacking up against its limitations: economic, geographic, and environmental. One of the oddities of the Geffen wing is that it serves as a deeply nostalgic homage to a linear city that is quickly becoming something else. A shrinking number of Angelenos still experience L.A. as a place defined by pure freedom of movement; they may be the same people who sit on LACMA’s board.

To cruise the boulevards with the top down, soaking in the Hollywood sign and Googie architecture, is now a sentimental luxury. Los Angeles—especially along the Wilshire corridor—is growing denser by the year. Just west of LACMA, the neighborhoods of Koreatown and Westlake rank among the most urbanized in North America, with more than 30,000 residents per square mile. These city dwellers don’t own convertibles. They navigate a hostile city as best they can.

The long-delayed Wilshire subway will have a stop at LACMA and is officially set to open later this year. From there, the D Line will continue through Beverly Hills, Century City, and UCLA in Westwood, breaching the barrier of the 405 and nibbling at the edge of Brentwood. Red Metro Rapid buses cruise up and down the boulevard, and more Angelenos are becoming apartment dwellers. So far, the Los Angeles Metro Rail system has quietly laid 109 miles of track. If the Geffen wing resembles an airport terminal—well, LAX also has a Metro stop now, completed just last month.

Urbanization works its inevitable transformations, despite opposition from those clinging to a 20th-century, suburban-utopian rebuttal to older cities. The attachment of Angelenos to the car, the detached house, and the private garden retains its near-religious power. The result is a privatized city—really, a constellation of cities—that has historically resisted even rudimentary infrastructure improvements that might civilize its environment for pedestrians.

The cultural complex that includes LACMA, the Petersen Automotive Museum, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, and the La Brea Tar Pits is a 20-minute walk up Fairfax Avenue to the Los Angeles Farmers Market and the Grove, Rick Caruso’s showpiece shopping mall. Nobody would call it a pleasant stroll. The jutted sidewalks are too narrow, putting pedestrians precariously close to four lanes of roaring traffic. The streetscape—the edge of the Park La Brea residential development, parking lots, blank walls, a Jack in the Box—is forbidding.

Los Angeles has been most successful in adapting to its Mediterranean environment through its extraordinary panoply of private residential architecture. It is now begrudgingly accepting the need for public spaces, clustered housing, and clean, safe, and reliable mass transit. The cruel joke is that no city in America could be more conducive to walking and cycling than L.A., thanks to its mild climate and the even flatness of the streetscape as it slopes away from the coastal ranges. The problem is that humanizing its environment means chiseling away at the lion’s share of space thoughtlessly given to cars.

Abundance activists bemoan the slowness of housing construction, but L.A. contains hundreds of acres of underdeveloped land—not at its environmentally fragile edges, but in the miles of low-slung mini-malls, parking lots, and gas stations along its desultory boulevards. These corridors cry out for transformation into more civilized urban forms: garden apartments with lush central courtyards; wide, well-maintained sidewalks shaded by mature trees; planted medians; and dedicated bus and bike lanes. Angelenos who rely on the nation’s largest bus system might finally have modern, comfortable shelters to wait in. L.A.’s urban lattice-work could knit the city’s storied residential districts together, rather than separating them.

The Geffen wing, in local architectural tradition, is a show-off. It’s not a reconciliation to changing urban realities but another performance. It turns your head, like the movie star at a neighboring table. But beyond that, its relationship to the rest of the room—Los Angeles—is more uncertain. Angelenos, traumatized by wildfires and the Trump administration’s military incursions, will welcome it. Architecture cannot do the work of healing a city alone. Still, there are plenty of examples of daring new buildings that revitalize the communities around them.

Instead, the L.A. conveyed by the Geffen wing is its midcentury heyday. In its curving evocation of the Space Age, the building is appealingly retro. With its spread-out, all-on-one-level square footage, it might be a souped-up 1960s ranch house. Windows that make the structure as much about what you can see outside as what’s displayed inside—a challenge for a museum—are archetypically Californian. L.A.’s famed Case Study residences, like Pierre Koenig’s view-grabbing Stahl House, are in its DNA. John Lautner’s Chemosphere (Malin House) could be part of the same Mars colony.

But those were private residences, not public works—set in the rustic environs of the Hollywood Hills. They hover above the city, on its wild margins, to take in the view, while the Geffen wing lands in the middle of the action. LACMA’s context is innately urban. Rather than embrace that, it still seems inclined to ape the Getty, which has not one but two spectacular hillside campuses.

In another city, the LACMA site might call for a more traditionally urbane gesture—a building that honors the street rather than pouncing on top of it. (In both climate and cultural disposition, Los Angeles would be better off copying Rome than Moonbase Alpha.) But L.A. is not like other cities. In Exposition Park, closer to downtown, MAD Architects has created an even more literal spaceship in the under-construction Lucas Museum of Narrative Art. The designers say the building floats above the city grid like a canopy—but it might just as well be preparing for liftoff.

The Lucas Museum nods to the environment with gardens that spill across its undulating roof. The Geffen, with its flat top, makes no such concessions. In a city where a vast desert of concrete already roasts beneath the Southern California sun, it offers up even more heat-conducting blankness. On an early September afternoon, the LACMA campus—which also includes the stark plaza showcasing Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass, Bruce Goff’s Pavilion for Japanese Art, and Urban Light, Chris Burden’s Instagram-friendly lamppost forest—can be blistering. The best California architecture is deferential to nature: not simply framing it for another eye-popping view, but placing human structures in harmonious relationship with it.

Perhaps LACMA will soften its grand statement with smart landscaping. Palms—used here and everywhere as a metaphor for Southern California—are not native to Los Angeles, nor do they offer real shade. Still, they have an uncanny effect on the Geffen wing and the streetscape. It’s called glamour.

Los Angeles, more than any city, knows that buildings can have star power. It’s taken longer to understand they can also be good citizens. The new LACMA arrives at a precarious moment—for the city and the world. Tourism, a key American industry, is threatened by Trumpian hostility to outsiders. Museum funding is in crisis. Scholarship is plagued by political antagonism. Natural disasters, economic volatility, and civil unrest threaten Los Angeles both as an engine of entertainment and as a place of ordinary habitation. There may be no more critical time for cultural institutions to open their doors wide—to everyone.

The critics are right, of course. The Geffen wing tries too hard. There are places where it should swoop and soar but, thanks to cost-benefit analysis, it clomps. It’s too big and not big enough. It bombastically tries to please the crowd, then makes excuses with faculty-lounge vocabulary. And all this before a single priceless work has been hung on its undulating walls. It’s not Meier’s Getty, or Gehry’s Disney Hall, or Moneo’s Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels. It’s not John and Donald Parkinson’s Union Station. But it is a swaggering new building for Los Angeles—a big swing, an act of hubris, and a million little cuts of compromise.

We ask buildings to do too much. But the cities that host them depend on quieter essentials: clean, safe streets; affordable housing; good schools; sunlit piazzas; boulevards that bloom. Still, visitors will come—to admire the art, to have lunch, to take photos, to smile at the view. And they’re right, too. Sometimes a thing is just a thing—and for all its imperfections, it can still be necessary.

And even, yes, marvelous.

Yours ever,

Tod Hackett

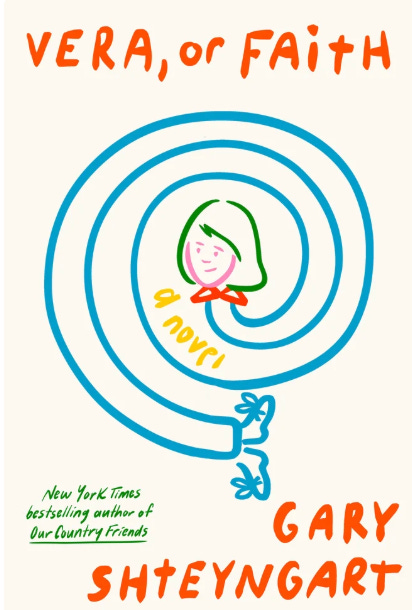

Vera, or Faith by Gary Shteyngart

We fell hard for Vera Bradford-Shmulkin, a bright, anxious 10-year-old trying to hold it all together—for herself, her loved ones, and an increasingly dystopian America. We feel you, Vera! Her troubles unfold in a creepy near-future where some people have more democratic rights than others and sleek tech smothers every human interaction.

But hold up! Like Roald Dahl’s Matilda before her, Vera isn’t having it. Just because life’s not fair doesn’t mean you have to grin and bear it! Half-Korean, half-Russian, 100 percent American, Vera becomes a pint-sized voice of resistance. Along the way, she—and Shteyngart—skewer all the things that bring us down: anti-immigrant prejudice, the smugness of Moncler-jacket tech bros, and the grinding march toward a reinvention of feudalism.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to CultureWag to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.