Chasing Ghosts

Our obsession with the Princess of Wales is all about persona. The person remains a mystery.

Long ago, in Pembroke Square, I glimpsed a mirage.

She flashed by within a few feet of me—voluminous blond fluff of hair, octuple scull for a nose, neon blur of workout togs—flanked by thick-necked minders, who bundled her into a Range Rover. Lady, nose, and centurions were off like a shot, deserting a clutch of photographers, who shambled into the street, haplessly snapping into the mist. This was my introduction to Diana, Princess of Wales, at the height of her scandal and fame.

We were neighbors in those days. Diana’s digs were just the other side of Bayswater Road, in Kensington Palace, while I shared a damp bedsit with half the population of New South Wales. On fleeting first impression, I was embarrassed for both of us. It was John Major’s Barbour-drab Britain, and a princess was too shiny a prize to fit into it. I didn’t know anybody who had much good to say about the royal family. Callow me, I wrote off its most famous member as a checkout line distraction.

The thing then was to be snobbish about Diana. The Australians I lived with saw her routinely, on runs to Wetherby, the junior school for her boys. It was a bit of a joke, that we colonials eked by in Withnail and I conditions, while not far away, an archaic pageant played out. If you were a modern person post-Thatcher, the Windsors were an eye-roll. Not long after my sighting, I happened upon a huge display of royals books at Waterstone’s in Notting Hill Gate. I thumbed through a vast album, documenting every outfit Diana had worn to public events since her engagement, a progression from ribbon-bedecked potato sacks to cocktail dresses that introduced the world to her knees. I left the shop with the novel The Queen and I, by Sue Townsend, in which the Windsor assets are seized and the clan is packed off to a Midlands housing estate. The going delusion was we’d outlast them all.

So many things I didn’t know! One was that the princess was about to do more damage to her in-laws than any Militant Tendency antimonarchist could could hope for. Another was that in nearly destroying the royal family, she actually stoked fascination with the institution, boosting its longevity. Lastly, I had no idea that I would spend a portion of my future life as a magazine editor burnishing her posthumous legend. People have always underestimated Diana.

Twenty-four years after her death, she is having a moment, which somebody craven termed The Dianassance. It began with Emma Corrin’s portrayal of the Shy Di-era princess in Season 4 Netflix’s The Crown, an impersonation that captured her darting glances and a speech pattern that might called aristocratic deflation (a language of mournful little puffs, like air being drained from the tire of a Rolls-Royce). It continued with Diana the Musical, now being hooted off Broadway—“If you care about Diana as a human being, or dignity as a concept, you will find this treatment of her life both aesthetically and morally mortifying,” wrote Jesse Green of the New York Times. It continues with Pablo Larraín’s Spencer, released earlier this month, starring Kristen Stewart as a hounded, haunted royal.

Larraín, who directed Natalie Portman as a White House hostage in Jackie, gives us The Princess in the Tower, tormented to madness by icy palace drones. It’s an expertly crafted horror show, starring a woman pinioned by public fascination, something Stewart, another shy person who rose to fame at a young age, may have an inkling of. The performance goes beyond goofy hats and Candle in the Wind martyrdom. The Diana of Spencer isn’t beyond scheming to save herself, but unlike her, we know the tale ends with a funeral cortege. “It absolutely speaks to her resonance,” Stewart told Variety of the awards buzz her portrayal has won. “It just won’t stop reverberating.”

Echoes overwhelmed mortal woman long ago. For what do we know of Diana, the person behind so many images, anyway? She was a devoted mother. She had a lovely smile, and unlovely demons. She looked great even in ridiculous clothes and had pedestrian taste in pop music. Her short life was lashed with luxury and misery. Christopher Hitchens, gleeful ointment fly, wrote her off as a “Bambi narcissist” and compared her funeral rites to the Nuremberg rallies. It’s the minority view. Whatever her flaws, Diana’s enduring appeal is that her heart seemed to be in the right place. In terms of a legacy, that is the mic drop.

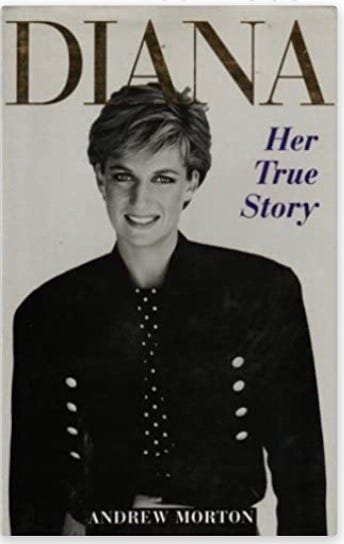

The great appeal of saints is their suffering, and Diana suffered cinematically. We know this because she told us so—in cries for help, and acts of vengeance, leaked from the inner sanctum. Hers was a guerrilla war, that relied on unnamed sources and surrogates as agents. The ur-text of Spencer grievance is Andrew Morton’s 1992 biography, Diana: Her True Story, which she covertly supported, the book that made her breach with the royal family public. Had Diana access to social media, such a liberation campaign might have pummeled us all into apathy. Instead, traditional publishing dropped them like an enormous bomb, which the tabloid press then sprayed around like shrapnel. All without a direct word from her.

In 1995, Diana did speak, in a Panorama interview with Martin Bashir, which the BBC has now apologized for (according to the Beeb, it was negotiated in a “deceitful” way using forged documents — another betrayal in a life defined by it). Dodgy ethics aside, the Bashir interview exposed the royal family in an unprecedented way, but it also revealed Diana as a damaged person. It remains startling to watch. The princess speaks elliptically, avoiding eye contact, alluding to mysterious conspiracies. She holds her head at a painful tilt, and tucks in her chin, like henpecked fowl. Until that point, the official Diana had been largely conveyed in pretty photos and carefully proscribed conversations (usually alongside her husband). When the smoke cleared, the queen gave the nod to a divorce.

Whatever tricks Bashir played, Diana told people at the time she knew what the outcome would be. Taken together, Morton’s book (which promulgated a separation), and the BBC interview (which ended a royal union), extricated her from an impossible circumstance — “Well, there were three of us in this marriage,” is about as direct as she ever got publicly — and blasted the reputations of Prince Charles and Camilla Parker-Bowles to kingdom come. The Crown has introduced a more nuanced point of view of a very complicated love triangle, but it’s never a good idea to pick a fight with a tragic heroine. Diana always gets the last word.

Had Diana lived, she would now be a 60-year-old grandmother, with many more triumphs and humiliations behind her. This would be a blessing to two sons who suffered a terrible loss, but it might also have liberated her from glamorized stasis. An older Diana would have likely been a society fundraiser, going to luncheons in a gold-button suit. She might have become a Mrs. Simpson type, living in sybaritic exile with a second husband, or a third. She could have been a Brexiteer, or gotten herself labeled a Karen (check your privilege, princess). That individual would surely have made enough mistakes to alienate some segment of the public. She’d finally be human, not merely an epic cautionary tale.

The current Diana stories tend to focus on her exploitation by the ultimate patriarchal system (even if the world’s greatest matriarch is its figurehead). This aligns neatly with a view now in vogue, but it’s silly, because Diana was hardly a revolutionary. She never sought to burn down the house she had provided an heir for, but to shore up her position within it. Her rebellion was not ideological, but the result of having been, as she quaintly put it, rather badly let down.

That is a Victorian way of framing infidelity and associated cruelties, but she did not lead a modern life. Her thrashing against a hermetic existence—self-harming, bulimia, maladies, acting out—would have been entirely recognizable to powerless women who lived a century before. Diana was raised in an antique manner, in an unhappy family more aristocratic than the one she married into. A finishing school dropout, she was betrothed to a man in his thirties when she was a virgin of 19—precisely because she was a virgin of 19. Somehow this arrangement was spun as the great romance not of 1881 but 1981, after the sexual revolution and the peak of second wave feminism. She was indeed a fairy tale princess, in all of its darkest aspects.

Diana transcended her trials because was old fashioned in another way: She was a star. Despite a rarefied upbringing, she had much in common with more ordinary latchkey children of her era. She innately understood loneliness because she endured it. Suffering made her sensitive and instinctively empathetic. These touchy-feely qualities are said to be in short supply among chilly Saxe-Coburg-Gothas. All of it came in a package that was very easy to sell. Diana liked Lionel Richie, and had an exalted version of an average mall girl hairdo. One jaded editor I knew described her as State Fair Pretty, not threateningly beautiful. She liked to give hugs! In contemporary terms, these attributes might translate as basic. They made her incredibly famous.

Her kind of stardom may no longer be possible. It requires considerable withholding, something contemporary celebrity does not allow for. Adoring hordes caught mere flashes of their so-called People’s Princess. They couldn’t reasonably expect to know her, but they liked the projected blend of extraordinary and ordinary qualities. This was possible because Diana was not available on demand. Palace machinery may have imprisoned the Princess of Wales, but it also cosseted her. The masses fell in love with an eternal persona. The vulnerable woman caught in the harsh light of Bashir’s interview is another matter.

One of my earliest jobs as a reporter was covering protests against the press in the wake of Diana’s death. The rage at the media (old hat nowadays) was bracing and childlike. Who were the paparazzi anyway, but low-rent hitmen for a ravenous public? The anger, and those piles of flowers and cards—a good part of that was expiation of guilt. Within a few years, I was going to meetings at Clarence House and Buckingham Palace, helping to shape mythology for a brand that needed the Windsors as a profit center (and they needed it back). I edited a book called The Royals: Their Lives, Loves and Secrets. In it are pages devoted to Diana’s dresses, year by year. It sold very well.

In the midst of this, the writer Peter Morgan began his long, dramatic excavation of the royals, first with The Queen, and now with The Crown, which has had a miraculous, humanizing effect. YouGov, which polls a fickle British public about the Windsors, routinely finds Elizabeth II and William to be the most popular family members. (Having left her audience wanting more, Diana transcends earthly favorability ratings). When surveyed, majorities of young respondents still tend to say they would do away with the monarchy. That happens to be the real fairy story.

The great tragedy of Diana, warts and all, is that she was condemned by crushing fascination. Long before her death, it relegated her to a kind of phantom zone. She was cheated of many things, not least the comfort of seeing her stardom fade.