For Your Consideration: Melvin J. Kaminsky

When Civilization Crumbles, Be Grateful it Gave Us Mel Brooks

In case of apocalypse, we’re stuffing a vault full of cultural treasures. First into our meltdown-proof capsule: Brooklyn’s universal antidote for gloom.

Mel Brooks likes to say: Tragedy is when I cut my finger, comedy is when you fall in an open sewer and die. How funny, dark, and true! Great jokes speak to life’s torment and pettiness. Good comedians have the fortitude to tell them.

These days, all the world’s a primal scream. So, we’re making a list of people and things that still make this tattered civilization worthwhile.

First up: The former Melvin James Kaminsky. Relax, he’s not dead yet! We just wanted to remind you that you share this planet with a 98-year-old ray of sunshine. (If you’d like to send a card, his birthday is June 26).

Mel Brooks knows Hitler can be made hilarious. He’s mined boobs, schlongs, the Spanish Inquisition, and the N-word for punchlines. Brookisan humor riffs on Russian literature, Hitchcock, Star Wars, and flatulence. He's weathered deprivation and grief and remains an unforgivable ham.

Emulate him.

Brooks was born on a kitchen table in a Brooklyn tenement in 1926. When he was two, his father, Max, died of tuberculosis, leaving his mother Kate to support four boys on piecework from garment factories. She doted on Mel, the baby. He was a sickly kid, but his four big brothers watched out for him on the streets of pre-artisanal Williamsburg. To defend himself, he developed a motor mouth.

Here’s an origin story Mel Brooks tells: When he was nine, his Uncle Joe took him to see Ethel Merman in Anything Goes. Joe drove a checkered cab (Mel got a free ride into Manhattan by lying on the floor in the back, where taxi inspectors wouldn’t spot him). Way up in the nosebleeds of the Alvin Theater, he first heard Merman’s booming mezzo-soprano:

You're the top

You're an Arrow collar

You're the top

You're a Coolidge dollar

You're the nimble tread

Of the feet of Fred Astaire

You're an O'Neill drama

You're Whistler's mama

You're camembert!

Broadway actors didn’t use microphones back then, but Merman’s voice sent Cole Porter to the rafters. That was all it took; the kid told his uncle he was going to make it in show business. Which really was a laugh. Nobody in Williamsburg worked on Broadway. They pushed racks down Eighth Avenue or sat behind sewing machines.

He wouldn’t be put off. By his teens, he was in the Borscht Belt, working as a busboy at the Butler Lodge. He went to school, stealing gags from comics who played the resort circuit. In time, Brooks landed a gig as a tummler, performing bits for guests poolside. Once, he loaded rocks into a pair of cardboard suitcases and pretended to be a salesman at the end of his rope. Business is no good. I don’t wanna live! he wailed, plunging off the diving board.

The crowd roared when his derby hat floated poignantly to the surface. Then a lifeguard dove in and saved him. Too many rocks.

The Mel Brooks Story, written and produced by Mel Brooks, skips merrily from Coney Island to the Catskills, from World War II to Your Show of Shows. The reality wasn’t so jolly. He doesn’t dwell on how his mother denied herself food so her kids could eat, or how his brother Lenny, a B52 gunner, was shot down by the Germans and held as a prisoner of war. Brooks joined the army out of high school and found himself in the Battle of the Bulge. In devastated Europe, he marched past the corpses of so many other boys, stacked in piles along the roadside.

Death is the enemy of everyone, even the Nazis, he told himself. To get through, he locked eyes on the horizon and sang the Al Jolson number “Toot, Toot, Tootsie (Goo' Bye!).”

At the war’s end, he was making other G.I.’s laugh as part of a performing troupe. Back in New York, he found a gig writing for Sid Caesar, one of the first great television stars. It was exciting but unpredictable work. Once, the volatile Caesar dangled him from a window ledge for complaining about working in a smoke-filled hotel room. Brooks cheated death and made it in TV comedy.

By the early ’60s the run with Caesar was over, and so was his first marriage. He was barely scraping by when “The 2,000 Year Old Man,” a sketch he developed with fellow writer Carl Reiner, became a sensation. Brooks played the title character as a cranky alte kaker (I have over 42,000 children — and not one comes to visit me). The routine inspired a series of hugely successful comedy albums.

His real stroke of luck was falling for somebody way out of his league. Brooks fell for Anne Bancroft when he saw her rehearsing a song and dance routine at the Ziegfield Theater. They found one another wildly entertaining from their 1964 marriage until her 2005 death from uterine cancer. “He makes me laugh,” she said. “I get excited when I hear his key in the door. It's like, ‘Ooh! The party's going to start!’”

Hollywood brought Brooks a global audience. After creating the spy spoof Get Smart with Buck Henry, he established himself as a screenwriter and director. His first picture, The Producers (1967), terrified major studios. Nobody would touch a satire about a Nazi musical. Somehow, it found a distributor and went on to win Brooks an Oscar for best screenplay. Its 2001 reinvention as a Broadway musical garnered 12 Tonys and sealed its reputation as one of the most influential comedies of all time. But really, it all boils down to this:

The miracle of “Springtime for Hitler,” is that it was created just 22 years after the end of the most catastrophic war in history. It made light of atrocities many audience members barely survived. But they understood what modern people seem to have forgotten: The best way to poke the devil in the eye is to mock him. “I tried to get even with Hitler,’ Brooks said. “By taking the mickey out of him.”

Shrinking nightmares down to jokes was the secret sauce. If goose-stepping thugs can be reduced to a prissy chorus line, all the horrors of human existence can be shouldered—Toot, Toot, Tootsie, Goo' Bye!

In Blazing Saddles (1974), Brooks sent up old Westerns by casting Cleavon Little as a sheriff sent to protect a racist frontier town. It hit theaters 10 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Saddles could never be made today and barely got made then. Warner Bros. suits ordered Brooks to take out everything offensive—horse-punching, racial slurs, sexual innuendo, all those farts—and the director dutifully took notes. When the meeting was over, he threw them in the trash.

He got away with it because he trusted his instincts and the audience. And there was something else. A Mel Brooks comedy can be gleefully crass, but it’s never cruel. Beneath a fusillade of terrible gags, there is a child’s reverence for Hollywood myth. Comedy, executed by a remarkable company that included Zero Mostel, Kenneth Mars, Gene Wilder, Madeline Kahn, Marty Feldman, Harvey Korman, Peter Boyle, Gene Hackman, and Cloris Leachman—is a Trojan Horse for hope.

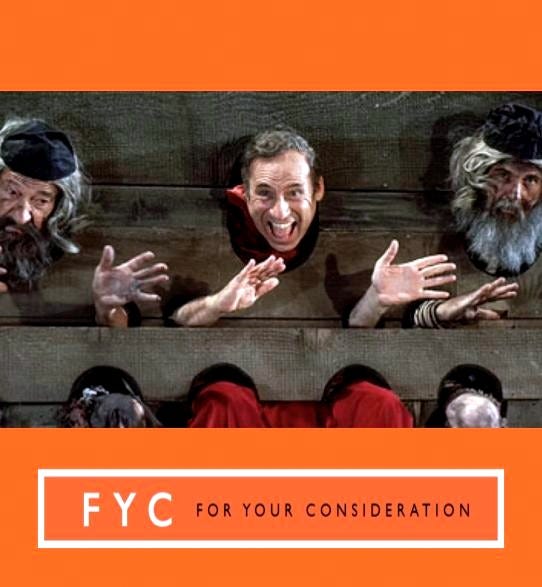

Young Frankenstein (1974) gets James Whale’s 1931 version of the monster dancing to “Puttin’ on the Ritz.” Silent Movie (1976), High Anxiety (1977), Space Balls (1987), and Robin Hood Men in Tights (1993) are more love letters to the movies from a kid at heart. The History of the World pictures spoof the big names and give the best lines to the little guys. Like everything else we endure, the Inquisition is just another show.

In the 20th Century, a boy could be born into poverty, survive a terrible war, and find Hollywood fame. He could meet the love of his life, lose her too soon, and still find absurdities to laugh about. He got on with things, because what other choice is there? And he helped millions of other people muddle through, too. It’s a good operating system for all the centuries to come.

Maybe there are mornings when Mel Brooks stares into the void and doesn’t find it so hilarious. Perhaps his children and grandchildren are exhausted by all the silly one-liners. But he rallies for the rest of us, pointing out that things have never been especially wonderful, and could always be worse. For example, you could fall into an open sewer and die. That would be tragic—for you, anyway. Give the rest of us a second to find the laugh. —Richard H. Thorndyke

CultureWag is the brainchild of JD Heyman, former top editor at People and Editor-in-Chief of Entertainment Weekly (among other gigs), and staffed by the Avengers of Talent. Our goal is to cover interesting topics with wit and integrity. We serve smart, funny recommendations to the most hooked-in audience in the galaxy. Questions? Drop us a line at intern@culturewag.com.

If somebody forwarded you this issue, consider it a coveted invitation and RSVP “Subscribe.” You’ll be part of the smartest set in Hollywood, Gstaad, Biarritz, and Father’s Office, which serves the best burger in the known universe.

“Easy reading is damn hard Wagging.” — Nathaniel Hawthorne